Declan T. FitzPatrick

I've been lucky to be around some of the most amazing mentor teachers and colleagues any teacher could ever hope for. Unfortunately one side effect of being exposed to extraordinary teaching is feeling the gap: the gap being what I should be doing and what I know how to do.

Recently I've been working with middle and high school ELA teachers to implement reading and writing workshop. The end goal is clear to us. We know we want to build highly engaged classrooms where "learning floats on a sea of talk," where students read and talk in small groups and write for each other and for real audiences in authentic forms. Our struggle comes with what to do first.

Here's what I'm currently thinking:

Response Writing

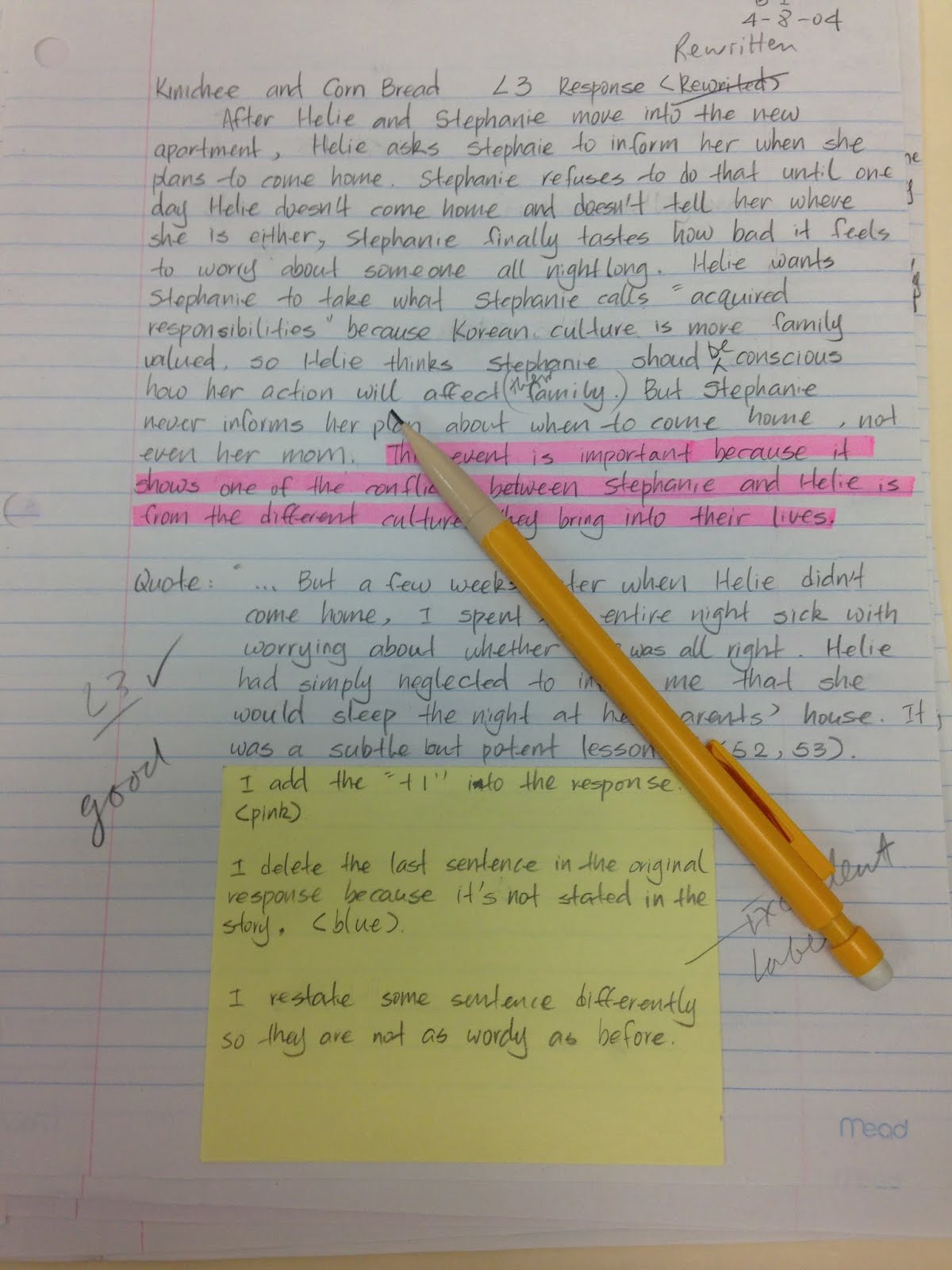

The simplest and most significant change I ever made in my classroom was to focus on student response writing. In the spring of my first year of teaching, I was out of ideas and exhausted from daily planning. I asked my students to write simple responses to each reading assignment for Lord of the Flies. I had no idea what my requirements ought to be except that they had to choose a moment or an event or an idea from the reading, write about it, and explain why it was significant to them. My students were suddenly engaged and seeking feedback. I was completely reenergized. I found that I could examine student responses and give feedback in a way that was meaningful to the students and useful for our goals.

I've been working on that form, format, and feedback with students and teachers ever since.

Captures Student Thinking

The first and best benefit to shifting to response writing is that it breaks me from constantly having to devise exactly the right set of questions for each chunk of text that students read. I find out a lot more about what is happening when students read on their own. Rather than focusing on compliance and correctness, I can focus on what cognitive work students exhibit independently. I can work hard to give feedback that describes what each student is doing successfully and what they should work on next. The conversation allows us to talk about significance and about what makes an idea significant. We propose ideas that might qualify, talk about them in small groups, rehash and combine them; add, move, delete, and edit ideas until we think they are worthy to submit to the whole class for discussion (or we run out of time). Groups craft and present bold statements or controversial questions and see what other people take-up and engage with.

Preparing for class has become an exercise devising structures that prompt more thinking and talking. Because students come to class with responses written, I can focus on uptake and on figuring out how to get to students to vet, exchange and complicate the ideas they write about.

Even with this freedom, all the student writing is entirely text dependent. They have to begin by identifying the moment in the text that is worth talking about. As students discuss their responses they revisit the text to validate and support more complex ideas.

Infinite Variation

The more my work has shifted to working with other teachers, the more resilient this structure appears to me. As long as the purpose of response writing is to choose a moment and explain why it is significant to you the format doesn't matter much. Some teachers want more deliberation and refinement and require longer responses that connect two quotes together. Other teachers want shorter simpler forms that generate more opportunities to practice. While experimenting with a teacher in a 9th grade class that emphasized independent reading we discovered that many students balked at the length of writing we were hoping for. At my co-teacher's suggestion we offered students the option of an action/reaction journal. They merely had to divide a page in half vertically and head each column with "When it said...," and "I thought...." They filled a page with four or more moments and their reactions to them. The students were still capturing their thinking about focused moments in the text, and many discovered that they had more and more to say about their thinking as they progressed. When students were ready they shifted (some naturally, others with much prompting) to the longer form of response.

Several teams of teachers have developed frames for response writing including the popular CQE (context, quote, explanation) that fits nicely into an analytic essay. I have created so many variations of format it would be impossible to catalog them. Response writing stays the same whether every student in class is reading the same text, or they are reading in groups, or they are reading independently. I almost never give students predetermined topics for responses. What changes is the way the responses are used during class time and the kinds of discussions we have about the concepts that connect our reading.

Foundational Shift

Adding response writing to a class doesn't require changes in texts, sequence, or seating, but it will facilitate a shift to examining significance. It's a shift that facilitates and encourages other shifts like structuring small group work, supporting independent reading, and providing descriptive feedback.

Comments

Post a Comment