I was a high school English and Reading teacher. I got thrown into teaching reading classes in a new job based on coming from a school district that had a reputation for providing “Content Area Reading” training. I taught reading classes for nine years. I was a high school reading specialist whose job was to provide job-embedded professional development to teachers who were trying to increase the effectiveness of their literacy instruction. Now I am a PK-12 curriculum coordinator working in a school district that is gradually implementing a reading workshop approach in middle and high school. If you have read Mosaic of Thought , In the Middle, The Book Whisperer, or Book Love and if you have already implemented reading / writing workshop in your middle and high school class this blog-post might be a simplistic rehash of what much more experience teachers have to say. Or it might validate your thinking.

If you are skeptical or curious about independent reading for secondary students and you haven’t read the experts, this post might provide some insight into the joys and pitfalls of supporting independent reading in ELA classrooms.

If you are thinking about adding independent reading to your class here’s my advice: do it. Tell your students to find a book and read it. Hold them accountable for making progress and proving to you that they are reading something they can do useful things with. Independent reading, when students choose books that they can and want to read by themselves, is something you can add to your classroom without disrupting much else and it will make a significant change.

I Was Doing it Wrong

When I began teaching reading classes I had never been exposed to reading workshop. I had no idea that there were teacher-authors I could read who would guide my way, and I did it all wrong. Despite the number of ways that I messed it up, my students still read a lot. I understand years later how very important that is.

1. Embrace Young Adult Literature

The first thing I wish I had known early on in my career was to embrace Young Adult Literature. Both the high school in which I taught, and the MAT program where I learned to be a teacher, emphasized that students are capable of engaging with complex texts written for adult audiences from another era. Skillful teachers create sequences of instruction that scaffold students through activity, discussion, and writing tasks that support students as they engage with complex texts. That’s still true, but it has a cost: reading volume. If students need to be scaffolded into and through a text, they need a skillful guide and they need a lot of time. The more mediated a text is for students, the less they are developing their skills as independent readers, and the fewer pages they are reading. When I began my independent reading class, I spent a lot of time trying to find books written for adults that high school students could manage by themselves. I only wandered into the world of YA Lit when my savvy-reader students introduced me to it. I began as a lit snob, thinking that there was too much good “real literature” for students to waste time with YA books. Now I am an avid reader and teacher of YA novels. They enrich my life and my teaching. Don’t be a snob. There is so much good writing for adolescents. It’s my job to find and promote it.

When I am collaborating with ELA teachers around curriculum development we continually revisit the balance between challenging texts and reading volume. Jeff Wilhelm has great advice: teach Romeo and Juliet; scaffold the students through the reading, direct scenes, compare movie versions, cast the play with celebrities, but while you’re doing all that work in the classroom have the homework (and some protected school time) be to read YA narratives about relationships and what destroys them. That is a elegant balancing of important difficult mediated text and large volume reading of engaging independently accessible text.

2. Time is the Great Equalizer

One thing that independent reading forced me to confront is that the readers in my classroom are very, very different from each other. Most of the time when the whole class was reading the same book, I did my best to ignore this fact. While I was still in the MAT program, George Hillocks, in an offhand comment, planted the seed that teachers really ought to know how long it takes for students to read what they assign. He suggested that teachers ought to do a timed reading with the class each time they began a new long text, and plan reading assignments equipped with that information. Every time I did this with my students, 9th grade or 12th grade, honors or remedial, I discovered that I had students who were reading 6 pages an hour and others who were reading 40. When I began teaching independent reading, I set a up a day for a timed reading at the beginning of the semester. Students had to have their book selection in class that day, read for half an hour, and record the number of pages that they read. We planned their reading schedules based around that number and the idea that they had to complete 5 hours of reading every 2 weeks, half in class and half at home. If they started a new text they had to do a new timed reading.

I wish now I had asked for more. Providing time, structure, and support for independent reading is motivated in large part by an emphasis on reading volume. If I had spent more time helping students find books that really engaged them, in creating next-read lists, in collaborating with each other to recommend and review books, I could have expected more. If I had monitored, supported, and celebrated volume, I'm sure many of my students would have read more. Much more.

3. Mini-lessons: Short, Focused, Responsive

So, I had two classes of 25 students all reading different things. I still needed to teach them something every day. I lucked into a book that had lots of very short readings intended as a sort of skill-a-day book for reading. I ignored the skills and taught strategies that students could apply to their reading: annotation, chunk and label, predict, question, infer, visualize. I now understand this model as the mini-lesson: a short segment of instruction that probably includes modeling and is designed for the students to apply to their reading. Working with middle school teachers as we implement a reading workshop model we have found the book Notice and Note by Beers and Porbst to be particularly useful in developing mini-lessons that embody the characteristics we are striving for.

Tight focus: a mini-lesson should have a single significant focus. As we collaborate we try to answer the question "What will the students be better at by the end of this lesson?" Then we tell the students.

Authentic tasks: a mini-lesson is almost always focused on doing something that adult readers actually do when they are reading something they have to understand. When we collaborate the first step is often to work the task ourselves. This runs any task through the reality check of whether adults would ever actually bother doing this work, and it generates a number of models that we can use to show the students the task in action.

Modeling with short complex texts: We are forever in search of great short pieces to use during mini-lesson. These can be as short as two sentences, or a as long as a page and a half, but the challenge is to find a text that is short and clear enough that it requires very little set up to introduce to the class. Modeling means "Watch and listen while I do this." The intent is to show quick clear examples of the kind of thinking and the kind of work we want the students to do. A model has to be fast, cheap, and dirty. Take too long or make it too elaborate, and you lose the focus on application. There is no set of instructions so clear that a quick model wouldn't communicate better. As Wilhelm says "Students don't know what I want them to do, until they see me do it.

Focus on application and reflection: The purpose of every mini-lesson is to to give the students a task they can apply during their independently reading time, and then reflect on, often with a partner. A series of mini-lessons over several days might model the same task over and over with different chunks of text, giving the students more opportunities to practice and take control of the strategy so that one day it may be come part of their independent repertoire.

Responsive: mini-lessons are an opportunity to teach what this group of students needs on this day. There are common skills, strategies, and tasks that will be a part of a class every time I teach it, but every group of students I'm faced with is different. I have a standard way that I introduce and teach response writing, but as soon as I have a sample of student work, I have to respond to what's in front of me. I can teach what these students (or most, or many, or some) of these students need right now. I wish I had been exposed to this idea and developed this belief earlier in my career. I was focused on designing the perfect sequence of lessons that would lift all boats. I work now on developing a repertoire of texts and mini-lessons that can be adjusted to address different needs for different groups of students.

4. Conference for Good Information

The teaching strategy I most regret not trusting and not developing is the reading conference. I talked one-on-one with my students all the time, but my focus was always on checking-in and clarifying instructions. I didn't expect to gather information from conferencing. I would have saved many students hours of wasted time if I had had a consistent plan of meeting one-on-one with a few students a day, to listen to them read two or three paragraphs, to talk about what they like and what they are getting from the reading, and to make recommendations if they needed to change books. In the past 5 years I've been in so many classrooms in which teachers have made this structure work, it's amazing. They figure out how the keep the rest of the class working, how to have a conversation with one student that doesn't distract everyone else, and how to work systematically through their rosters within the limited time constraints. No matter the preparation I put into helping students select texts for independent reading, I always had students who were secretly struggling with books they could not efficiently manage themselves. Listening to a student read for 1 minute, and asking them to talk about what they have just read unearths this reality and produces so many other rich benefits, I recommend it to anyone who will listen.

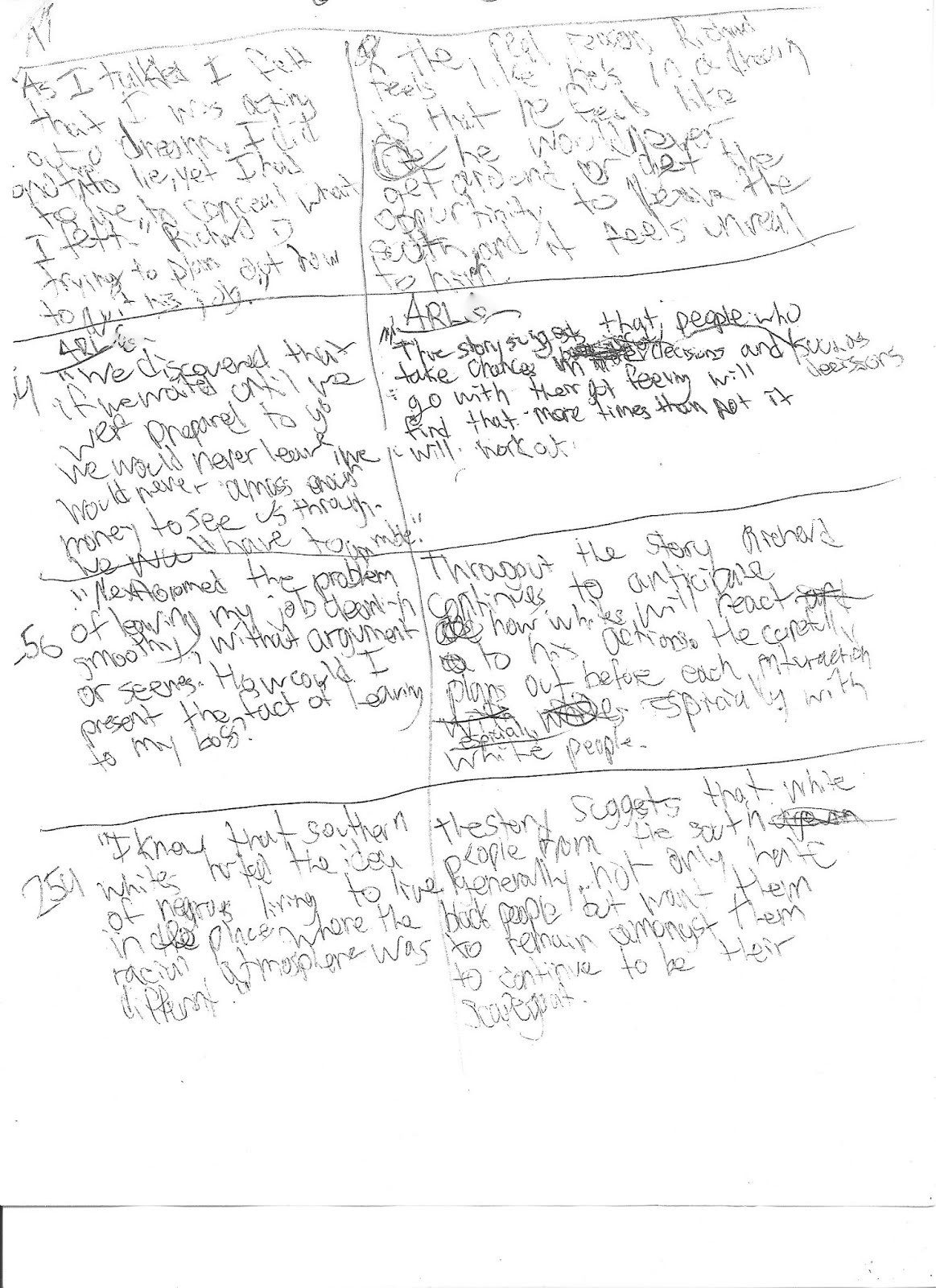

5. Response Writing

Teachers often raise concerns about holding students accountable for their independent reading. The normal impulse is to invent a project or essay to write once the novel is completed. Book talks and book reports especially ones without an authentic audience are painful for everyone and not helpful for assessment or accountability purposes. They are too easy to fake or to complete without a deep engagement with the text. Writing reviews especially for authentic audiences (like posting reviews on goodreads.com or Amazon) makes more sense to me and is useful for a very specific kind of genre study. My problem with these approaches though is that they require too much teaching and they are too hard for novices to do useful work with. It takes instructional time to teach the forum and format, to model high quality work, and to monitor student work as they progress. Independent reading is not supposed to take over the unit in my class. It is a habit and a practice that I am trying to foster in my students. Students need independent reading because they need to be consuming large volumes of accessible text. The students who read the most are the ones most likely to be successful in college.

The solution for me is response writing. I want students to capture their thinking about a small piece of text repeatedly and routinely. I want those responses to be useful as a starting point for small group discussion, and as way to capture and hold a thought that a student can come back to. After discussion a response can be added to, revised, edited, and made more complex. Students can pick up on an idea from a peer, make a connection to their own writing and write a more complex and thoroughly supported response. A collection of responses becomes a record of evolving thinking. An annotated portfolio of responses, tracking the student’s evolving thinking, increasing complexity, or developing skill in constructing a literary argument makes an excellent final project.

Reflecting on the Work

As I was planning for this post, I made a page of notes, intending to describe the struggles we are having making independent reading significant for our students. As I began listing what we’ve done and what we and what we are working on I was surprised by how much we’ve accomplished.

Elementary School

In the elementary schools our work with independent reading has been an important part of the school day for several years, ever since we began implementing a balanced literacy approach. Younger students have browsing bags, or boxes, full of books they can and want to read independently. Students read independently for minutes every day, younger students for fewer minutes than older. Teachers routinely teach mini-lessons about strategies or literary elements, and then expect the students to apply the ideas from the lesson to their independent reading and then discuss with a partner what they noticed during their reading. Currently teachers are working on adding student response writing to the classroom expectations.

Middle School

The visionary principal of our middle school restructured the schedule so that students could have 90 minutes of ELA every day. Teachers have taken advantage of this to routinely build in 30 minutes of independent reading day after day. In our last book adoption, we focused on purchasing classroom libraries of books that the students actually wanted to read. Having the books in the room was a necessary component, but it has taken years of deliberate work by dedicated teachers to integrate independent reading into the course work in a way feels connected and significant.

High School

Five years ago we added a course to the ninth grade at the high school. All freshmen, except the students enrolled in Honors English (who must be reading above grade level to enroll in the class), take a class called Academic Literacy. Modeled off the Reading Apprenticeship in Academic Literacy described in Reading for Understanding we built a class on independent reading structured into 4 units, each designed to emphasize a different kind of academic reading.

Writing this, I have to acknowledge that we have devoted extraordinary resources to independent reading. Teachers have worked incredibly hard to figure out the logistics and dynamics of engaging students in reading significant numbers of books and to integrate independent reading into instruction. But you don’t have to. It can be as simple as asking students to bring books they want to read to school, giving them time to read during the school day, and making sure that they do.

This is so helpful. Thank you for posting. In all the years I've taught English/Language Arts, I have almost never had kids reading their own stuff. It makes more and more sense the more I read about it - I don't know why I didn't do it earlier. In a future post, I'd love to hear more detail about your approaches to accountability for each student. Thanks again for this thoughtful and practical blog. -- Sarah

ReplyDeleteDeclan, great post! This is so informative, and you write convincingly.

ReplyDelete